The ire of two Prime Ministers

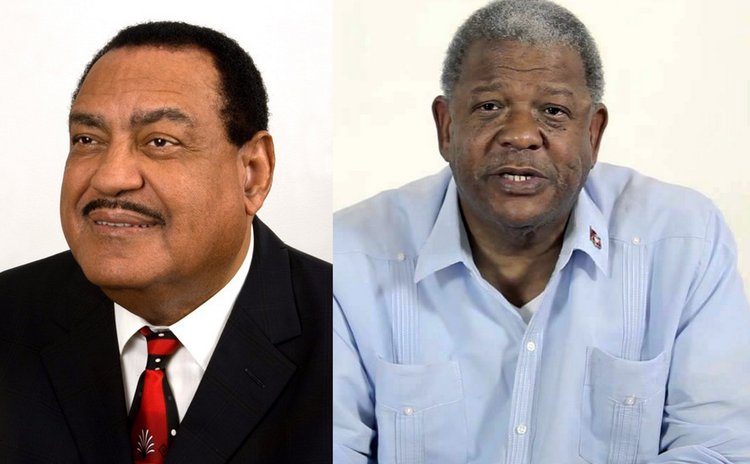

On May 29, two former Prime Ministers and leaders of opposing political parties in Antigua and Barbuda presented their nation's parliament with one of those rare occasions in which in a fiery debate, they were 'singing from the same hymn sheet' as the saying goes.

The occasion was the introduction in the House of Assembly of a Bill that sought to make it compulsory for the beneficial shareholders of vehicles for financial transactions, including companies and Trusts, to be known and registered, and for severe penalties to be applied when such information is withheld from regulatory authorities. The requirement for the Bill did not arise from local circumstances; it was a directive (euphemistically called 'a recommendation') from the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) and the Global Forum of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), that are the creations of the rich, industrialised nations to set global rules in financial matters.

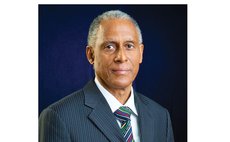

The two former Prime Ministers are Sir Lester Bird of the Antigua and Barbuda Labour Party and Baldwin Spencer of the United Progressive Party. Both men have wide experience of superintending every aspect of their country's affairs. In addition to being Prime Ministers - except for one brief period during Spencer's administration - they retained the portfolio of foreign affairs. In this regard, they both had up-front and first- hand knowledge of the several – and unending – incursions into the sovereignty of their nation by both the FATF and the OECD.

Given their experience of growing-up, resentfully, in a colony, where all the major decisions about their country were made in a distant and alien metropole, it is not surprising that both men place a high value on the autonomy that they consider their country achieved at its independence from Britain. So, the introduction of the Bill struck a discordant note with them. One might even say that the Bill 'stuck in their craw'; they appeared not to be able to swallow it easily, if at all.

In this connection, they joined in a chorus of protest – Spencer's belting to Bird's timbre. Neither man would have the Bill passed; both saw it as an imposition by external forces that would further injure their nation's financial services sector. Bird pointed to the continuing absence of a level playing field in the implementation of the FATF and OECD rules. He named powerful countries that ignored the rules they make and impose on others. And, both former Prime Ministers thundered that the present government should stand-up against the unfairness of the system and simply refuse to accept dictation from the rich and powerful governments.

Sir Lester is correct that there is one OECD country in particular that openly allows company incorporations and Trusts with no requirement to disclose beneficial owners. The result is that this business has move there to the detriment of other jurisdictions, but all are powerless to correct that wrong.

Forlornly, it was suggested by the two former Prime Ministers that CARICOM countries should jointly resist these impositions that disadvantage them and render them uncompetitive in the global financial system.

But, the horse has already bolted on all of these matters; trying to close the stable door now will accomplish nothing except a black-listing by any jurisdiction courageous enough to do so. When the opportunity for a solid CARICOM resistance to the FATF and OECD rules was ripe, governments failed to act in concert. In beggar-thy-neighbour policies in which government of Caribbean countries sought to escape the disapproval of the powerful, they abandoned solidarity for what they thought was self-preservation. So, they acquiesced to demands and distanced themselves from each other. To be fair some Caribbean governments were not involved at the time; they lingered under the impression that the OECD was after 'off-shore' banks and international business corporations. They failed to see the signs that, eventually, 'off-shore' and 'on-shore' would be blurred.

Wider alliances with countries in similar circumstances in the Pacific, Africa, the Mediterranean and even Europe, were not effectively forged. As usual, divide and rule tactics were employed by the powerful and they were effective. The consequence is that, by unrelenting policies of intrusion, the governments that created the OECD and FATF have managed to impose rules that now ensnare the world. The system is an effective form of control by the powerful over the weak.

In this connection, the shared ire of Sir Lester Bird and Baldwin Spencer over yet another demand by the FATF and the OECD is understandable, but futile. Nothing short of a movement by many countries to wrest control of the rules governing the global financial system from the OECD countries and putting it where it has always properly belonged – the United Nations – can or will change the present unfair structure. Such a movement would require trust and confidence among the governments that initiate the action. It would also require political courage and non-partisan political support within countries. And the chances of all that happening are utterly remote.

The present Antigua and Barbuda Prime Minister, Gaston Browne, was right, therefore, when he pointed to the consequences of non-compliance with the FATF and OECD rules. Antigua and Barbuda, acting alone, would be blacklisted as "un-cooperative" and appropriate penalties would be devised. For example, the current withdrawal of correspondent banking relations by US and UK banks would intensify and be adopted by other OECD governments, crippling the country's economy. Already several countries in the Caribbean (including Barbados, The Bahamas, Belize, the six smaller Eastern Caribbean countries, Guyana, Haiti, Jamaica, Suriname, and Trinidad and Tobago) have lost correspondent banking relations from the US and the UK. They now have to go as far as China and Turkey to settle their US and UK transactions. Subsequently, their costs of international transactions – with no guarantee of continued service in the future – has led to a rise of as much as 300 per cent.

The Antigua and Barbuda debate - with its blend of vexed idealism at impositions on the country's sovereignty and calm realism of its vulnerability – is probably replicated throughout the Caribbean. How these small states will survive in a global society, where power prevails over principle, will increasingly become the question of this Century for their political leaders, businessmen, diplomats, academics and journalists.

Responses and previous commentaries: www.sirronaldsanders.com

(Sir Ronald Sanders is Antigua and Barbuda's Ambassador to the US and High Commissioner to Canada. The views expressed are his own)